Thanksgiving: Myth vs. History

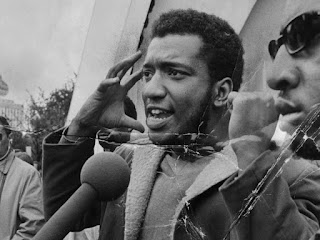

Dutch and English settlers band together in a slaughter of the Pequot tribe, 1637

When we are introduced to the mythic history behind Thanksgiving in elementary school, we are most commonly offered a blurry image of Native Americans and English Pilgrims coming together in peace over a bountiful harvest. This hyper-sensationalized narrative holds some truth, as a group of English Puritan settlers did have a celebration of harvest in 1621 with members of the Wampanoag tribe* at Plymouth, who had helped them learn to sustain themselves after a particularly devastating winter. This story, however, is not the event that culminated into the nation's first officially documented day of Thanksgiving. Janet Siskind dispels this misconception, saying:

"The celebrated historic feast in Plymouth clearly does not fit as a day of thanksgiving. It has been construed as a harvest festival, descended from an English custom of the Harvest Home (Hatch, 1978: 1053), a politically motivated feast to maintain the colony’s alliance with the Wampanoag Indians...The connection between these three days of feasting in Plymouth in the fall of 1621 and our celebration of Thanksgiving is purely, but significantly, mythological."

The real story behind Thanksgiving is much more sinister.

Known as the Pequot War, the Pequot Massacre, or the Mystic Massacre, the first documented "thanksgiving" celebration followed English and Dutch Puritan settlers' success in decimating the Pequot tribe in 1637. In the hours preceding daylight, the New England colonies orchestrated a surprise attack on the Pequot village, slaughtering any Indians in their path. The settlers, whose initial plan had been to overtake the village, faced strong resistance from the Pequots. As a result, the Puritans altered their course of action, ultimately burning the town to the ground. Over 400-500 men, women, and children alike were murdered, and any remaining survivors were later enslaved.

The the primary purpose of the attack was for the colonies to expand their operating territory. The Pequot Massacre was genocidal in nature, killing mass amounts of people. The attack operated as a punitive war, or a war meant to "teach a lesson" and instill fear in survivors and neighboring tribes. In other words, the murder of the Pequot Indians is but one of many examples of American terrorism.

The pilgrims eradicated the people of the Pequot tribe, and in celebration, the governor of Massachusetts Bay assigned an annual "day of thanksgiving" celebrating the massacre throughout the colonies. This day of thanksgiving was ordained as a commemoration of the slaughter of the Pequots for years following.

The Thanksgiving Day we now celebrate as a nationally recognized holiday was implemented by President Lincoln in 1863 in response to a letter written to him by Sarah Josepha Hale. It was initially adopted as a patriotic holiday in which Americans were encouraged to give thanks to God for all of the nation's blessings. The common story of the pilgrims and Indians was not tied to Thanksgiving for nationalistic purposes until years later, and was done so rather incorrectly.

Over 380 years later, the horrendous violence against the Pequots continues to be perpetuated when we forget about the blood that was mercilessly spilt under our feet. We mask the brutal realities of our history with more appealing mythical stories of peace and harmony in order to assuage our guilty consciences. Yes, it is uncomfortable to think about the acts of terror and genocide upon which this country was built, especially on a day which is celebratory for giving thanks and spending time with loved ones, but this remembrance is necessary. The erasure of this violence from the discourse of American history sustains systems of cultural imperialism, as the dominant narrative continues to effectively lock Indigenous peoples into harmful, dehumanizing stereotypes. The importance of remembrance of these events is exacerbated when we take a look at the current climate of the nation:

On Thanksgiving, we celebrate the pilgrims who came to America, fleeing from various struggles in Europe. America is a country that prides itself on the "good" immigrants who inhabited it after the mass decimation of Indigenous populations, yet while we sit around the table with our families today, there are children in cages at the border, wishing for nothing other than to see their loved ones again.

On Thanksgiving, we celebrate the "peaceful" feast between pilgrims and Native Americans nearly 400 years ago, yet on this day only a couple years ago, Indigenous people were being violently terrorized at Standing Rock. Today, as we carve our turkeys and pumpkin pies, police forces in Duluth are gathering over $80,000 worth of riot gear in preparation for their brutalization of Indigenous activists fighting against Enbridge's Line 3 pipeline. Not to mention the Wall of Forgotten Natives—a large Native homeless population forced to take refuge in the tent encampment on Franklin and Hiawatha in Minneapolis. How ironic is it that Indigenous peoples are not even allowed to take up space and live upon the land that is theirs in the first place? For these real, living, breathing people, there is no peace; they face systemic and institutional violence simply for existing.

And so, my friends, I leave you with this: Eat your turkey and your pumpkin pie. Gobble up your cranberry sauce, your stuffing, and your greens. Eat your corn and wild rice and give thanks to the Indigenous peoples who cultivated it. Give thanks for the blessings of the family you are able to see, and for safety from tear gas and rubber bullets. Give thanks for the warm house you are allowed to inhabit, and the soft bed upon which you lay your head at night. But please, this year and for years to come, remember the true history of the blood that was shed that night in 1637. Remember all the lives that were stolen by the brutalities of settler colonialism from the moment Columbus washed up on the shore of the Bahamas in 1492, up to the present. Resist the systems that will stop at nothing to render Indigenous people invisible.

Remember.

*The irony behind the mythological "first Thanksgiving" we most commonly celebrate is magnified when we take into account the fact that the second documented day of thanksgiving celebrated the New England colonies' annihilation of the Wampanoag tribe in 1676.

Sources:

The research for this piece was vetted by scholarly articles and other resources available to me through my university. For more information on this subject, see my list of sources below.

The Invention of Thanksgiving: A Ritual of American Nationality by Janet Siskind

Possession: Indian Bodies, Cultural Control, and Colonialism in the Pequot War by Andrea

Robertson Cremer

Man on the Street: What is Thanksgiving Commemorating? (accessed from Educators Reference Complete)

Comments

Post a Comment